“Pollution-by-zip code” has been the dismal realpolitik result of a practice that has been embraced for more than half a century by some of America’s largest industries, and by the regulatory agencies that are charged with their permitting and oversight.

Communities of color, tribal and indigenous communities, and economically depressed areas long have been targeted as sites for chemical plants, refineries, pipelines, landfills – the kinds of enterprises that generate toxic waste. As a trade-off, the corporations behind these projects usually promise jobs-jobs-jobs, which also helps to minimize or distract from local pushback. And historically, there’s been a tacit expectation that government regulatory agencies will be lenient when it comes to environmental oversight because, as the old adage goes, what’s good for business is good for America.

This has happened in Detroit, Michigan (48217) and St. James, Louisiana (70086) and Denver, Colorado (80216). You can probably think of localities where this is happening in the state where you live, too – there are seemingly endless variations on this pathological theme. These places have come to be called “sacrifice zones” – that‘s the term for areas that a society allows to be environmentally damaged for the sake of overall economic advancement – and these areas are almost always located in minority communities.

But over time, as an array of cancers and cardiovascular and respiratory illnesses have proliferated in stunning numbers among adults in these communities, and – even more heartbreaking – as the children in these communities are being diagnosed with everything from asthma to leukemia to developmental disorders, local residents – the survivors – are becoming increasingly vocal about the toll this is taking.

“Over the years, we started seeing different diseases happening to people,” Theresa Landrum, a lifelong resident of the 48217 zip code, said in a recent interview via Zoom. She began ticking off the maladies on her fingers.

“You name it, we have it: diabetes, emphysema, cancer, COPD, lupus, leukemia, kidney failure…” and she went on, running out of fingers before she ran out of maladies.

“I know somebody who died from every one of them,” she said – beginning with both of her parents, as well as neighbors, local shop-owners, teachers, and classmates. “When we grew up, so did our health challenges.”

Landrum is a cancer survivor. As are her sister and her aunt.

So she became an advocate for environmental justice in her community. It’s been slow-going and it’s been tedious. It’s involved knocking on doors, talking to neighbors, and advocating when she goes to get her hair done at the beauty parlor. It’s involved attending meetings even through her own bout with cancer. And it’s meant reading through hundreds of pages of corporate and legal documents containing budgets, projections, data – all written in what she calls “tech-ese.”

“Trying to hide something? Put it in print,” she noted wryly.

We’ll return to Landrum’s story later, but it should be noted that her experience as a person of color who is challenging corporate interests and government apathy in order to restore her community’s health is not singular. It’s being repeated all around this country in places from which middle and upper classes habitually avert their gaze.

It’s worth taking a step back for a moment to consider the history of “EJ” – the environmental justice movement. This has been a slow green wave that has been building power since the 1980s.

As far back as 1987, an eye-opening study conducted by the United Church of Christ’s Commission for Racial Justice demonstrated the disproportionate impact of polluting industries on communities of color. The concluding report correlated the locations of hazardous waste sites with the racial and socioeconomic characteristics of communities. On average, it found that in a locality that hosted a single operating hazardous waste facility, the minority percentage of the local population typically was twice that of communities without a waste site. And when an area had two or more facilities producing hazardous waste, the percentage of minorities living in the surrounding community was nearly triple that of communities that had no waste sites.

It was becoming clear that in America – “land of the free” – the geography of racism included not only the practice of redlining, but also an even more ominous environmental component.

Given the oil and gas fracking boom that’s occurred since that UCC study, there’s been a glut of new chemical manufacturing facilities coming online – well over 300 plants in the last decade alone, most of these sited along the Gulf Coast, in the heavily industrialized areas around Houston, for example, and along the stretch of the Mississippi River between Baton Rouge and New Orleans that has become known as “Cancer Alley.” You might be able to guess who’s living in those surrounding communities.

But that’s getting ahead of the story.

Twenty-nine years ago next month, activists from all 50 states, as well as Puerto Rico, the Marshall Islands, Canada, and Central and South America, convened in Washington D.C. for the first National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit. Sharing their stories of the air, land, and water contamination in their own communities, and energized by the stories of actions and advocacy that were being undertaken by their colleagues, Summit attendees developed 17 Principles of Environmental Justice that targeted both private enterprise and government as culprits. These activists asserted the right of all cultures and communities to participate as equal partners at every level of decision-making on environmental issues.

Shortly after the Summit, environmental sociologist Robert Bullard, then a professor at University of California-Riverside, compiled a book of essays about the environmental efforts of activists of color. In “Unequal Protection,” Bullard included stories of real-life struggles in the aforementioned Cancer Alley, and the barrios of Los Angeles, and Chicago’s South Side. There were chapters about the fight against PCBs in Warren County, North Carolina and the discovery of DDT in Triana, Alabama. All of these cases primarily impacted communities of color. And all of these cases resulted in residents organizing to confront their own government as well as the polluters, to determine liability for the problem and to seek redress.

As a book, “Unequal Protection” served not only to showcase these environmental efforts by activists of color, but also to frame these as elements of a collective movement, rather than isolated instances.

At around the same time, Congressman John Lewis, with the support of then-Senator Al Gore, introduced the Environmental Justice Act in Congress. It was the first piece of legislation to address the racial disparities in how environmental protections were applied. Despite repeated efforts on Lewis’s part, that bill never made it over the finish line.

In 2004, however, with Gore looking on as Vice President, President Bill Clinton signed Executive Order 12898, which signaled that the federal government should recognize and address the impact it was making on minority and low-income populations whenever it considered permitting of factories, energy production and transportation systems, as well as conservation of natural resources.

When Clinton’s successor, George W. Bush, came into the Oval Office, this effort lost steam, but it regained momentum when Lisa Jackson became the first black female chief of the Environmental Protection Agency under President Barack Obama.

During this same time period, many states were jumping on the environmental justice bandwagon, passing EJ legislation of their own. Despite the growing recognition of the importance of EJ, many of these laws lacked teeth, however, and follow-up studies suggest that in many places, these laws failed to make much of an impact.

Since the beginning of 2017, when Donald Trump became President, there’s been a major sea change, figuratively and literally, too. According to an analysis conducted by the New York Times earlier this year, the EPA and the Interior Department under Trump have dismantled scores of environmental rules on power plant and vehicle emissions, and on wetland, aquifer and wildlife protections. At the same time, this administration has loosened dozens of regulations on drilling and mining, while restricting the time allowed for environmental reviews.

Looking at the long list of rollbacks, it seems clear that the current executive branch of government seems hell-bent on environmental plunder, with an accompanying disregard for vulnerable populations. But there are some folks up on Capitol Hill who are working toward a very different result.

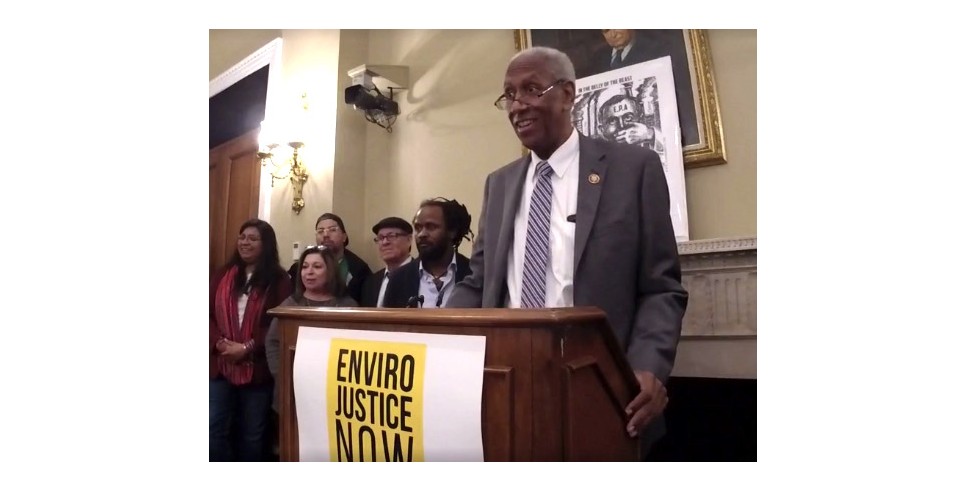

In June of last year, Congressman Raúl Grijalva (AZ-03), Chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, and his colleague Congressman A. Donald McEachin (Virginia-04) hosted a daylong convening in Washington D.C. They brought together environmental justice stakeholders from around the nation. There were fellow lawmakers in attendance like Representatives Deb Haaland (NM-01) and Rashida Tlaib (MI-13). There were scholars like Professor Bullard, now considered by many to be one of the fathers of the environmental justice movement. There were activists from teenaged to gray-haired.

And there were battle-tested directors of environmental nonprofits like Richard Moore of the Environmental Health Justice Alliance for Chemical Policy Reform, who confessed to the gathering, “We’re sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

But – just as the 1992 Environmental Leadership Summit had done – bringing people together in 2019 energized everyone all over again. In large part, that’s because the need for climate action has become too urgent for anyone to ignore at this point. But it’s also because Grjjalva and McEachin supplied an opportunity to take meaningful steps to do something about it. They announced the launch of a yearlong bill-writing project that depended on the input of attendees.

Their new Environmental Justice for All Initiative was reminiscent of the Environmental Justice Act first sponsored by Congressman Lewis back in 1992. The legislation would address how to remedy racial disparities in the application of environmental protections. But since Lewis had first introduced his bill, global warming driven by human-made emissions into the atmosphere has accelerated climate change in a way that is now tangible to all. Hurricanes Katrina and Sandy and Maria have happened. In the American West, the annual wildfire season is expanding in length and magnitude and frightening ferocity. And according to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the acidification of the world’s oceans is increasing drastically as the upper layers of oceanic waters are now absorbing some two billion tons of carbon dioxide a year.

In other words, it’s no longer just the people in those front line communities who are affected by the toxic byproducts of our industrial economy. Increasingly, it’s everyone.

But because the front line communities of color have been at this so long, they have become the experts in taking on the polluters.

When it comes to environmental injustice, Raúl Grijalva knows more than a thing or two. He’s lived in the same zip code in Tucson all of his life – and, yes, that zip code and the zip code just next door are Arizona’s hotspots for superfund sites, permitted emissions, unemployment, poverty – and now, the highest pandemic mortality rate.

“It’s a very proud, hard-working neighborhood – I’m glad I live there, just like all of us are,” Grijalva told a gathering of environmental justice activists recently. But like others who live in sacrifice zone zip codes, when news first came out about disproportionately high levels of cancer for women living in the neighborhood, and alarming numbers of deformities among newborns, state authorities first engaged in “blame the victim” behavior – suggesting to residents, Grijalva recalled, “that it was their diet, that it was their lifestyle, that they drank too much, smoked too many cigarettes, they were idle, they were not employed, so it was the community’s fault.”

It took more than three years before the EPA concluded it was actually pollution from a local industry that was the cause. The offending area finally ended up being designated a superfund site.

Before Raúl Grijalva ran for Congress, he had been active in his community for a long time. He’d served on the local school board. He’d gotten involved in a project to clean up chemicals that were leaking into the neighborhood from Davis Mountain Air Force Base. He’d also championed the Sonoran Desert Conservation Plan when he served on the Pima County Board of Supervisors.

And since being elected to Congress in 2002, Grijalva has been an outspoken advocate for protection of public lands, national parks, wilderness and Native American cultural sites.

The Congressman often favors wearing a sweater vest and bolo tie instead of a conventional suit. Maybe that makes him look more approachable. As Chair of the House Natural Resources Committee, he’s really focused on accessibility. Beyond enthusiastically encouraging his own constituents to get out and enjoy their beautiful public desert lands, he has worked to diversify decision-making in the environmental movement across the country. He’s done this by reaching out to underrepresented groups – women, African Americans, Latinx, and Native Americans – and welcoming their input.

As the other chief sponsor of the Environmental Justice for All Act in the House of Representatives, Donald McEachin calls himself Robin to Grijalva’s Batman. But in a recent phone interview, McEachin said that prior to 2005 he might have described himself as an environmental agnostic.

He had already been practicing law for many years, and had even served in the Virginia House of Delegates, when he decided to enroll in the Samuel DeWitt Proctor School of Theology at Virginia Union University in 2005.

“I had no idea I was entering into what could fairly be described as the religious left, a school that goes to great length to understand liberation theology,” he says now.

It was at seminary that he learned about creation care: “What is our role and what does God expect of us as we take care of this wonderful jewel we call the Earth?”

He received his Master of Divinity in 2008 and entered the Virginia Senate that same year. There, he said, he gradually became more conversant with environmental issues as they impacted everyday life.

“There might as well have been a little yellow book called ‘Environmentalism for Dummies,’” he said.

But as an ordained Baptist minister, environmental justice issues began to inform his politics.

“I try to emulate Jesus – his ministry was very concerned with what we could call today the working poor. And that’s what we’re talking about when we’re talking about the EJ community.”

McEachin refers proudly to constituents in Charles City County, within his own district, as an example of what environmental justice advocates can do.

A small rural county that lies between the Chickahominy and James Rivers, east of Richmond and west of Williamsburg, Charles City County has a majority-minority population of only about 7000 total residents, almost a fifth of whom live in poverty.

In 2016, the area was targeted by corporations wanting to build two large natural gas-fired plants there, located just a mile apart from each other. They also wanted to bring in a pipeline to serve the facilities.

With backing by then-Governor Terry McAuliffe, permitting at the state level continued apace before local residents even heard about the project. (Only half of the county had access to broadband internet at that point.) But as word began to get out, the locals came together as Concerned Citizens of Charles City County – C5 – to point out that they had zero need for the energy these plants would provide. Furthermore, they were concerned about the disruption that the construction of these industrial enterprises would bring to their rural county.

But most importantly, the C5 folks did not want the permanent disruptions they foresaw for their community.

Founded as a community in 1613 – yes, you read that right – Charles City County today markets itself as an “Unspoiled, Unhurried & Uncommon Place.” Massive industrial plants would not be a good fit with the existing tourism-based businesses there that focus on history, hiking, fishing and hunting. Nor were residents enthusiastic about the potential air, noise and water pollution that would come with an industrial presence. They mounted a years-long opposition campaign, writing letters and submitting testimony.

Accustomed to speaking from his pulpit at Cedar Grove Baptist Church, the Reverend Wayne Henley invoked some of the rhetorical flourishes of his profession when he testified wholeheartedly against the plants earlier this year before a State board.

“Hear the disenfranchised today, hear the marginalized today, hear the minority community today, hear the voices of our ancestors screaming from their graves today and for once, think about the common man. Make a statement for the people today and hear their voice, because their voice matters.”

At the same time that this local advocacy was heating up, environmental justice and the environment in general were getting a boost from state lawmakers hard at work in Richmond.

This past spring, they passed legislation that commits Virginia to joining the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, and which puts Virginia’s energy generating plants on a steady carbon emission reduction diet.

In addition, the Virginia Council on Environmental Justice was codified into law. A governor-created Council already existed, but this new law will protect the Council from being vulnerable to the whims of whoever holds the state’s highest office in the future.

Also, lawmakers passed the Virginia Environmental Justice Act. As mentioned earlier, other states had passed EJ legislation previously, but sometimes saw little effect. Virginia’s new law laid out targeted details: it established an Interagency Working Group on EJ and a Commonwealth policy with regards to EJ. It also provided EJ definitions.

And these were put to the test just a couple of months later in the cases involving Charles City County.

Taylor Lilley is an environmental justice attorney with the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, which provided support to C5 in this case.

With Virginia’s new Environmental Justice Act, she explained, “We had a definition for EJ, we had an idea of what the Commonwealth wanted when it came to EJ, and we had an opportunity to make it an integral part of the way the State Corporation Commission considered that pipeline.”

With that in mind, C5 and other opponents of the pipeline went before the State Corporation Commission, a permitting body, in May, and demonstrated all of the opportunities that the applicants had missed in soliciting EJ input.

That, along with the public’s growing inclination to shift away from fossil fuels, caused the first domino to fall early this summer. After investing heavily in the pipeline proposal, Dominion Energy and Duke Energy Corporation announced that they were canceling the project.

Since then, the State Corporation Commission has put a hold on additional aspects of the infrastructure project that would support the two gas-fired plants, citing concerns about financing and – here it is again – the failure of plant backers to consider EJ factors.

Following these hopeful developments, Lilley underscored the importance of the efforts of C5 folks and other grassroots volunteers, over months of hearings against powerful and moneyed interests, to tell their stories and have their voices heard.

“They’ve got endless juice and so much passion for their home and the place,” she said.

As a young attorney in the field of environmental law, Lilley was inspired by these local residents who refused to have their neighborhoods fouled and turned into sacrifice zones.

But it is precisely this growing activism on the front lines, by people who are refusing to be victimized any longer (the link to Black Lives Matter seems clear) that may be the key to the profound and necessary shift in America’s mindset concerning our responsibility for environmental health.

“Environmental justice asks us to be collaborative. It asks us to set aside ego and to think of new ways to involve each other,” Lilley said.

At a recent webinar reviewing recent environmental justice victories around the Chesapeake Bay watershed, McEachin agreed.

“If we can make EJ personal, get to know folks who live in those [front line] communities, it will give a better appreciation for why we fight the fight.”

So let’s circle back to Theresa Landrum, the cancer survivor and EJ advocate in the notorious 48217.

Loyal to her family and her community, she lives on the same block where she grew up. She’s happy to tell you about her childhood and the neighborhood of her youth.

Her dad grew up as an orphaned sharecropper in Tennessee, and her mom was from Tennessee, too. Both were part of the Great Migration, as Black Americans moved north to find more opportunity and perhaps less prejudice. Of course, there was redlining – the practice of excluding people of color from buying homes in desirable areas – happening in the north. But in Ecorse, a community that had been annexed into Detroit in the 1920s but maintained its own identity, Blacks were allowed to buy property after World War II.

Landrum, the youngest in a family of five children, was born in one of the first Black-owned hospitals anywhere, staffed by all African American doctors.

“We had Black business owners, a Black bakery, Black florist, Black cleaners, a Black police officer, a Black principal…” and – not too far away – one of the first African American-owned skating rinks in the country.

“It was an African American mecca down here.”

She described the street where she grew up – it’s the street where she still lives. Then as now it features brick homes on tidy lots.

Back then, Landrum said, “The trees were so big and full and leafy that they connected over the street, and every backyard had a garden and multiple fruit trees. There was a huge strawberry patch at the corner house, and in back of us the Dewey family grew prize-winning Golden Delicious apples that they presented at the fair every year.”

To get into Detroit proper, her family would go a block over to Electric Street and ride the trolley. She remembered they had to cross three bridges before they got into downtown.

But things began changing significantly when she was still a little girl. In her classroom one day, she heard that some of her friends were going to be leaving because their homes had been taken by eminent domain – Interstate 75 was going to be built right through the neighborhood.

“I went into the cloakroom and cried,” Landrum said.

When she was young, there had been a woodland just a couple of blocks away, home to raccoons, rabbits, possums and turtles. Those disappeared forever with freeway construction, and once the land was cleared, for the first time they could see an oil refinery across the way that was adding storage tank after storage tank after storage tank. Industry was booming – there were steel mills and car manufacturers and salt mining companies and other petrochemical plants. There were smokestacks belching smoke, back in the days before emissions were regulated. And there were pipes discharging untreated wastewater into the river.

“We noticed that things were changing – how the garden wasn’t producing as much,” Landrum recalled.

The kids would write “wash your car” in the grime that showed up on the cars in the neighborhood – there was so much pollution, people were washing their cars every day, but the grime would be right back there the next morning, for kids to write in again. Sometimes the stuff would be sticky.

The trees in the neighborhood started to die off, and not only that, the neighbors started getting sick. By the time Landrum was 9 years old, her own mother was making frequent trips to the hospital, and was diagnosed with throat cancer a few years later.

But it was the 1980s when Landrum really began to find her footing as a neighborhood activist. She learned that the new owner of an old salt mine located beneath the neighborhood wanted to convert the mineshaft into storage space for toxic waste.

“Many of the older people had taken a tour and wanted to go along with it. But I was wait-wait-wait,” Landrum said. “Salt is a corrosive. You start throwing plastic containers of a toxic substance into a corrosive environment, what’s going to happen? They said, ‘OK, young lady, why don’t you go down and talk to the city council?’”

So she did, successfully presenting an argument that her densely residential neighborhood needed to be protected from this threat. Time marched on.

In the 1990s, her neighborhood began to experience mini-earthquakes. There were rumblings underfoot and the sound of explosions on an almost daily basis. People started finding cracks in their chimneys and foundations. Sinkholes started appearing in yards. And nobody knew why this was happening.

Landrum started nosing around and found out that the salt mine had been sold again, and the city council had given the new owners the right to blast under their houses, because people unknowingly had sold off their mineral rights.

She started reading all the fine print in the permits and discovered that the company was using the same mixture of explosives that Timothy McVeigh had used in the bombing of the Federal Building in Oklahoma City.

She convinced the city council to drop their agreement.

By the turn of the century, Landrum was involved in another fight – this time with Marathon Oil, the oil refinery that had installed dozens of storage tanks within view of their residential neighborhood and, it turned out, was emitting unregulated poisons .

But that company is hardly the only offender – there are more than 30 heavily polluting industries surrounding Landrum’s community, spewing more than 150 different kinds of chemicals into the air.

The neighborhood is a nonattainment area for both ozone and sulfur dioxide – that means the air quality in the place she has lived her whole life persistently exceeds allowable standards for human health. And as health experts will tell you, the cumulative effect of exposure to multiple toxins can shorten lifespans significantly.

In an effort to restore health to her neighborhood Landrum has, at this point, engaged in decades of environmental activism – protesting, marching, and attending hundreds of meetings. She’s fought a system that has allowed the worst polluters to do “self-reporting,” and she’s outraged now that the current administration has been rolling back all of the hard-won regulations that were supposed to protect people.

It’s safe to say she is not a Trump supporter.

But she also knows where the most essential test lies: it’s with the people.

“How culpable are we for this climate crisis? We have been greedy takers. We have not been good stewards of Mother Earth,” Landrum said. “Our carbon footprint must be reduced.”

In February of this year, just before the COVID-19 pandemic shut things down for a spell, Chairman Grijalva and Representative McEachin introduced their Environmental Justice for All Act at a press conference on Capitol Hill. They’d spent the previous year gathering feedback on a draft of the bill. Using an online platform called POPVOX, they had welcomed comments, criticisms, and even line-by-line edits from EJ advocates on front lines all around the country. They got some 350 substantive comments, according to a staffer with the House Natural Resources Committee. And nearly every single one of those was incorporated into the bill to make it stronger.

Some of the bill’s chief features include:

- Amending the Civil Rights Act to allow private citizens and organizations that experience discrimination (based on race or national origin) to seek legal remedies when a program, policy, or practice causes a disparate impact;

- Providing $75 million annually for research and program development grants to reduce health disparities and improve public health in disadvantaged communities;

- Levying new fees on oil, gas, and coal companies to create a Federal Energy Transition Economic Development Assistance Fund, which would support workers and communities transitioning away from greenhouse gas-dependent jobs; and

- Requiring federal agencies to consider health effects that might accumulate over time when making permitting decisions under the federal Clean Air and Clean Water acts.

The Congressmen’s plan was to tour the country with this legislation, hosting seminars over the late summer and early fall in some of the areas hardest hit by environmental injustice, and featuring some of the advocates doing important work in each of those locales. Their itinerary included Michigan, Louisiana, Houston, New Mexico and Los Angeles.

But when COVID-19 made traveling inadvisable, they switched to a schedule of virtual conferences instead. The first online event focused on the concerns of Michigan environmental activists. It included powerful testimony from Landrum, former Detroit Health Department head Abdul El-Sayed, Flint Rising director Nayyirah Shariff, and Sierra Club organizer Justin Onwen.

The next two sessions were scheduled for Louisiana and Houston, but Ma Nature and Hurricane Laura had other plans. Those meetings had to be canceled and will be rescheduled for later this fall. Sessions in New Mexico and Los Angeles are happening early in September, just as this article goes to press.

Given the current political make-up of the Senate, and the President who now occupies the Oval Office, Grijalva and McEachin harbor no illusions that their bill can be passed this year. However, just before she was picked by Joe Biden to become his running mate, Senator Kamala Harris signed on to become one of the bill’s sponsors in the Senate. And Grijalva and McEachin hope that with that important election coming up in November, the political landscape next year may be more conducive.

“It’s all about the vote at this point,” McEachin said. “We have got to make sure that we vote in a green legislature. If the person that you’re talking to doesn’t understand that environment is THE most important issue of the 21st century and doesn’t understand that EJ has to be a centerpiece of that effort, then they’re really not fit to represent you. “

He continued in an optimistic vein. “I do know this… if we use this time between now and January to educate our countrymen about the importance of environmental justice, about how we got here, and where we need to go, we will be in fine shape in January to get this bill signed by President Biden in the first 100 days.

“As the Scriptures say, do not grow weary in well-doing.”

Barbara Lloyd McMichael is a freelance writer living in the Pacific Northwest.