NOTE: I usually try to write from an outline, with a tight-knit argument. But I ask you now to accept a collage of thoughts thrust upon me by recent experiences, and ask yourself if your experiences are similar.

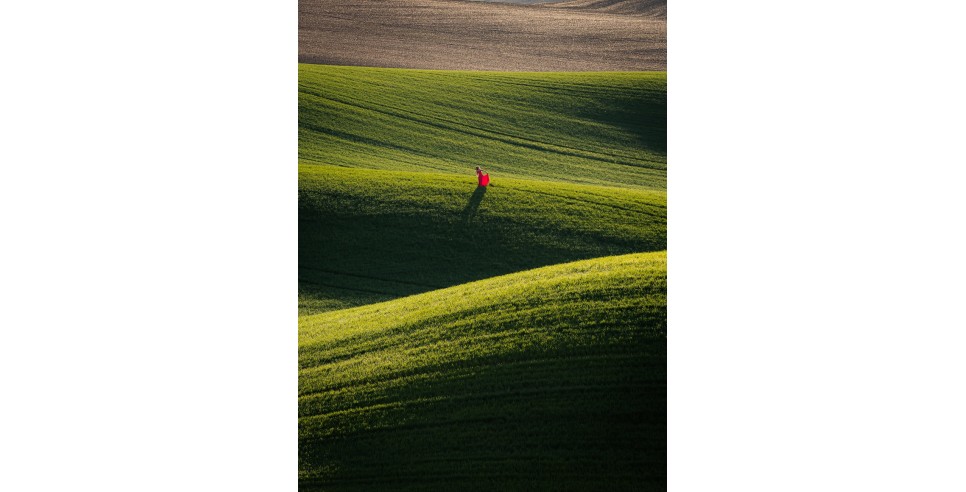

Can beauty save the world, as Dostoevsky imagined? Is it the best bet to do so, As Doug Tompkins wagered? In an ugly time, is it the truest of protests, as Phil Ochs declared? I can only say that it has transformed me and that its ability to change cynicism to reverence and to make people happier, healthier and kinder is well-documented. I made that case last month in Luxembourg, the world’s richest country by measure of per capita GDP, where the economic institutions of the State are reassessing how to assess wellbeing and its sources and invited me to speak.

Before I got to Luxembourg, I enjoyed delicious servings of Europe’s ageless beauty with friends who live there. The Gothic spires of Prague from the broad Vltava meandering under bridges. The lushly-forested sandstone hills along the Elbe on the German border. The completely restored Baroque splendor of Dresden, risen from the ashes of its World War II leveling by Allied bombers in the same shapes and colors are before the war, a testament to the power of beauty’s demand to be maintained. The blue Baltic at Gdansk whose beauty (or the drab ugliness of Stalinist apartments) must have inspired Walesa’s Solidarnosc shipyard revolt. The glassy reflections on Polish lakes and canals only miles from the Russian border, where lush forest hung over our tourist boat like Spanish moss in Mississippi bayous. The Old Town of Olsztyn, where my Polish friend showed me castles and arches and cobblestoned squares and quiet pathways along the Lyna River.

Public transportation we can only dream of in America—frequent buses, trams and trains—took us everywhere quickly and almost without effort, in cities free of the tents of the homeless, the addicts, the mentally ill muttering on street corners and even the occasional crack of gunfire that I have become accustomed to in Seattle, where I live. I came back to a city growing increasingly Third World in appearance, wondering what the quest for beauty might do to bring back hope and trust.

In Luxembourg, I spoke of the many ways that beauty heals. Take, for example, the poorest parts of Philadelphia, where University of Pennsylvania health specialists led interventions to clean up nearly 1500 vacant lots, garbage and needle-strewn concrete, and abandoned houses, investing to convert them to pocket parks with trees and greenery and in many cases vegetable gardens.

The result—a 29 percent reduction in gun deaths; more than 30 percent reduction in crime; only half the incidents of serious mental health; people feeling 58 times safer to venture outside. An impact so powerful the study concluded that a dollar invested in cleanup and “beautification” saved 70 in other costs. The study concluded that we are too focused on treating individuals. We’d gain far more by changing circumstances and particularly by making it possible for people to live among green space and beauty. Many other studies have come to the same conclusion.

I moved to Seattle for its beauty—the natural beauty of the Sound, the Cascades, the Olympics—and I know people still come here for those things. Certainly, our natural surroundings are a plum that corporate recruiters hold out to prospective employees. And they flock here from the world over, only to watch the city they’ve come to treat beauty as an afterthought.

How do I know beauty is not only a subjective thing, a cultural construct of Western sensibility? I can see it with my own eyes. Two weekends ago, I went to Olympic National Park with my family. On the two short trails we enjoyed, throngs of people walked beside us. At the entrance station on the Ho River, I counted a hundred cars lined up to enter. The last of them would be waiting for two hours as rangers allowed cars to enter only when others were leaving because the parking lots were full. At the Sol Duc Falls Trailhead, where there is no entrance station, cars circled the lot looking for a space. The trails themselves were a United Nations of people, at least as many of them People of Color as White. Young and old, grandmothers from India, visiting their Microsoft and Amazon-employed children, lifting their saris above the dust of the trail, Hispanic children screaming excitedly by the waterfall as their parents watched the rainbow spray with awe.

I’ve been especially tuned to the power of beauty to transform as I’ve been directing a film about the life of Stewart Udall—www.stewartudallfilm.org. America’s greatest Interior Secretary spoke of the “economics of beauty” and what it might do for America. From Lady Bird Johnson’s beautification campaign, which Udall encouraged her to start, to the protection of clean air and water (now threatened by our Supreme Court) to the creation of dozens of new national parks, monuments and wildlife refuges, Udall believed in America the Beautiful, and his policies brought Americans together across political lines. Even then, in the 60s, he warned of a time like today when our parks would be loved to death and we would need more and more of them.

Perhaps a new national crusade for beauty--City Beautification Days, cleanups, interventions like those in Philadelphia, a new commitment to the Land and Water Conservation Fund, establishment of new parklands, wilderness areas, urban trails and bikeways, scenic river protections, might help bring America together. Can’t we pay unemployed coal miners to reforest the denuded mountains of Appalachia as the CCC did in the Thirties. Can’t we tie housing for the homeless to some kinds of programs that allow them to earn sweat equity and dignity by beautifying the neighborhoods around them. Is all of this too much for America? I hope not.