William “Bill” Powers lived about thirty miles northwest of Denver in Longmont, a town famous for its craft breweries, but we never talked about beer. We talked about Yonkers. He grew up in Yonkers, same as me. We were working-class kids. And we shared awe and a touch of pride for where we had come from—a small city on the Hudson River with a funny-sounding name.

Growing up in working-class Yonkers gave us humility. Pride too. We were proud of who we were, but our pride was always kept in check. We tried to do the right thing and worked hard, harder than we needed to, unlike the kids who went to fancy private schools and had a sense of entitlement sprung from nannies, tutors, and homes in all of the right neighborhoods.

Living in the shadow of New York City, working-class kids grew up far too soon, often taking care of parents and younger siblings, and getting jobs by the time they turned fourteen. Not being responsible only invited trouble and, sometimes, it meant dying young. Bill and I knew of plenty of kids who died from overdoses, car wrecks and violence. But being young and responsible was no assurance of having a long, healthy life. A lot of young men from Yonkers wound up in Vietnam. Some died there.

Bill’s description of his experience in Vietnam was pretty low key. He was seventeen when he enlisted. He served with the 1st Infantry Division (Big Red One), Alpha Company, 1st Battalion 28th Infantry in the United States Army. He wrote, “I turned 18 that November and in January 1967 I was in Vietnam assigned to the First Infantry Division as a combat rifleman.” I later learned that Bill was awarded a Combat Infantry Badge, a Bronze Service Star, Vietnam Campaign Medal, Congressman's Medal of Merit, New York State Cross of Gallantry, the Good Conduct Medal and a Purple Heart.

Bill’s description of his experience in Vietnam was pretty low key. He was seventeen when he enlisted. He served with the 1st Infantry Division (Big Red One), Alpha Company, 1st Battalion 28th Infantry in the United States Army. He wrote, “I turned 18 that November and in January 1967 I was in Vietnam assigned to the First Infantry Division as a combat rifleman.” I later learned that Bill was awarded a Combat Infantry Badge, a Bronze Service Star, Vietnam Campaign Medal, Congressman's Medal of Merit, New York State Cross of Gallantry, the Good Conduct Medal and a Purple Heart.

After Bill came back from Vietnam, he worked with the Westchester County Police before joining the Yonkers Police Department in 1972. He worked as a police officer for 23 years and rose to the rank of Detective First Grade. Bill retired from the Yonkers Police Department in 1993 and moved to Colorado. He went on to have a second career with Boulder County Sheriff's Office, where he worked for sixteen years.

In true Yonkas speak, Bill and I talked about the aroma of fresh baked rolls and buns from Busy Bakers, Café Trento, and Mengers. We knew all of the joints—the Midget Bar, Edgar’s Pub, and where kids like us hung out on Lake Avenue, Lennon Park, the North End, and Untermyer Park. It was widely rumored that Yonkers had more pizza places, bars, and bakeries per capita than any other city on earth. We believed that, and you know how it is with rumors, especially rumors originating in Yonkers, they usually turn out to be true.

Bill never regretted his move to Colorado but he really missed a Yonkers neighborhood. He wrote, “I could walk down to Lake Ave and have the bakery, the Hoagie Hut, a couple of delis, soda fountain shop, butcher, hardware store and local pharmacy. Here in Colorado you go to a grocery store and it’s a one-stop shop. I know times change, but the memories don’t change.”

It was Bill’s memories of Yonkers that had prompted him to reach out to me. He had read my books. I didn’t have the heart to tell him that no one in the traditional literary world was particularly interested in my books about Yonkers. I cannot fathom why they want this working-class town to remain in the dark. It was as if Yonkers would always be forced to live in the shadow of New York City.

After months of exchanging emails, I met Bill during my zoom author chats sponsored by the Yonkers Public Library. A lot of other Yonkers kids showed up too—all grown up now and still remembering our past. Bill reconnected with Barbara O’Connell, who used to live on his same block next to Sacred Heart High School. Bill met Tim Phelps, another Yonkers kid who had worked at Morsemere Market on Palisade Avenue in the North End.

Today Tim Phelps lives in Allenspark, Colorado, a small town that is located in the forest near Rocky Mountain National Park and Estes Park. Tim had been a teacher at Eagle Rock School for many years. As an integral member of the school, he was part of a team that recruited Native American students to the school. He was adopted by an elder of the Oglala Lakota Pine Ridge Reservation in 1996.

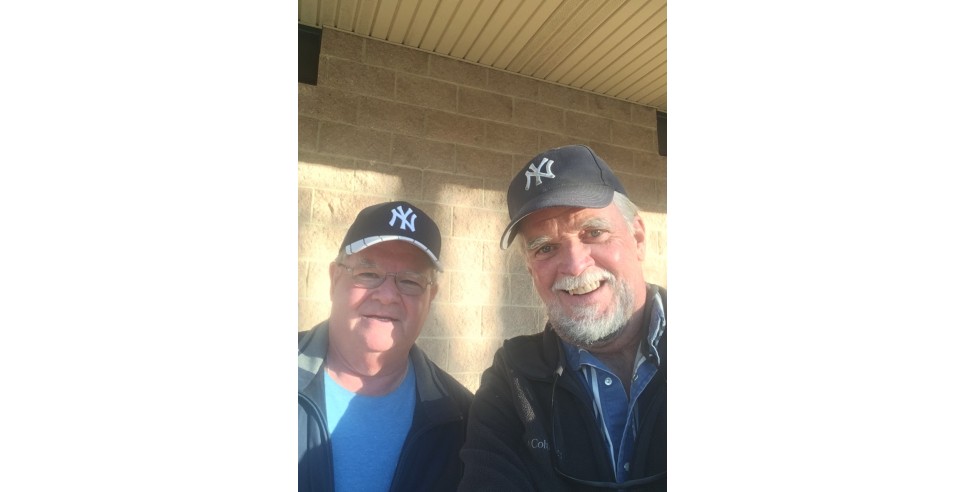

Tim was and has always been an activist. He stood tall during the protests at Standing Rock. And Bill was a cop, a highly decorated cop, recognized for his bravery. Their politics might have been different; and if it was, it didn’t matter. In Colorado, Bill and Tim got together. They both stepped out of their cars wearing Yankees ball caps. Bill and I continued to exchange email and with Tim, too. Bill had become more than a fan or someone who wanted to reminisce about Yonkas, he had become my friend.

Colorado was on my fly list, and not as wishful thinking. My daughter, Katie, lives in Denver and was expecting her first child. I kept telling Bill I would get to Colorado soon. He was looking forward to reading Book Three in my Yonkers trilogy. He wrote, “Time marches on but as you say memories are forever. Looking forward to Book Three. Also looking forward to the day we can actually sit down in person and re-live those memories.”

I booked my trip to Denver for November. I was a month out from that trip when I got the news that Bill Powers had died suddenly. His son, Tom, wrote to me to thank me for spending time with his Dad. “He loved talking about old Yonkers and very much enjoyed your book.”

As a writer, I never know if my work is making a difference in anyone else’s life. I was very moved to find out that my work captured an era that Bill Powers had lived through, now long gone, and that was meaningful to him, and to other kids like us. Yonkers kids. There is nothing more important to me than knowing that I was able to move our “Yonkers” out of the shadow for the world to see.

In his final act of love for his city, Bill Powers returned home from Colorado to Yonkers to be buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery. In one of his last emails to me, he wrote, “We only go around once in life and when you get to a certain age you begin to think and dream about your younger years and growing up.( I think it’s called the aging process). I know you can’t bring them back, but your books have allowed me to go back in time and remember a life and culture that molded me into what I hope is a good, decent human being. I wish those times were here today. Keep up the good work and looking forward to the future books.”

Author’s postscript: I flew to Denver on the Sunday before Thanksgiving. On the morning of Thanksgiving day, my Katie gave birth to my first grandchild, Wyatt. I kept feeling like something was missing. I did get to Colorado. I just didn’t get there in time. Bill Powers was gone and I would never meet him, not in this life, anyway. But in the long run that was okay. We would always have this Yonkers thing between us and the other kids like us.